Hilma af Klint: Engaging and Transcending Scientific Discovery

2023-07-04

I went to the Tate Modern the first day I traveled to London. I got there in the afternoon, right before it rained, walking over the Millenium Bridge.

I was quite exhausted. First stop, the espresso bar.

The main thing I wanted to see was an exhibit on Piet Mondrian* and Hilma af Klint. I honestly went because I recognized Mondrian’s name from the one architectural history class I took in college. Had no idea who Hilma af Klint was.

This was the first thing I saw in the exhibit:

Maybe I was tired. Maybe I’m just dumb. But I really thought the quote was intentionally shown with parts of it missing. And then I walked closer to the wall. Turns out, the quote is fully visible up close:

And that’s probably when the espresso kicked in.

All of the sudden, I realized it was the way the text paint reflected some of the gallery lighting, causing the text to appear like parts were missing from afar. What was visible to you depended on where you stood relative to the wall. And just as the quote suggests, I became self-aware of the nature of my own perception. I was in awe.

I asked a museum staff whether this was intentional and they weren’t sure. I’d like to think this was an intended feature, because this interplay between perception, nature, and understanding was a consistent theme in af Klint’s works on display.

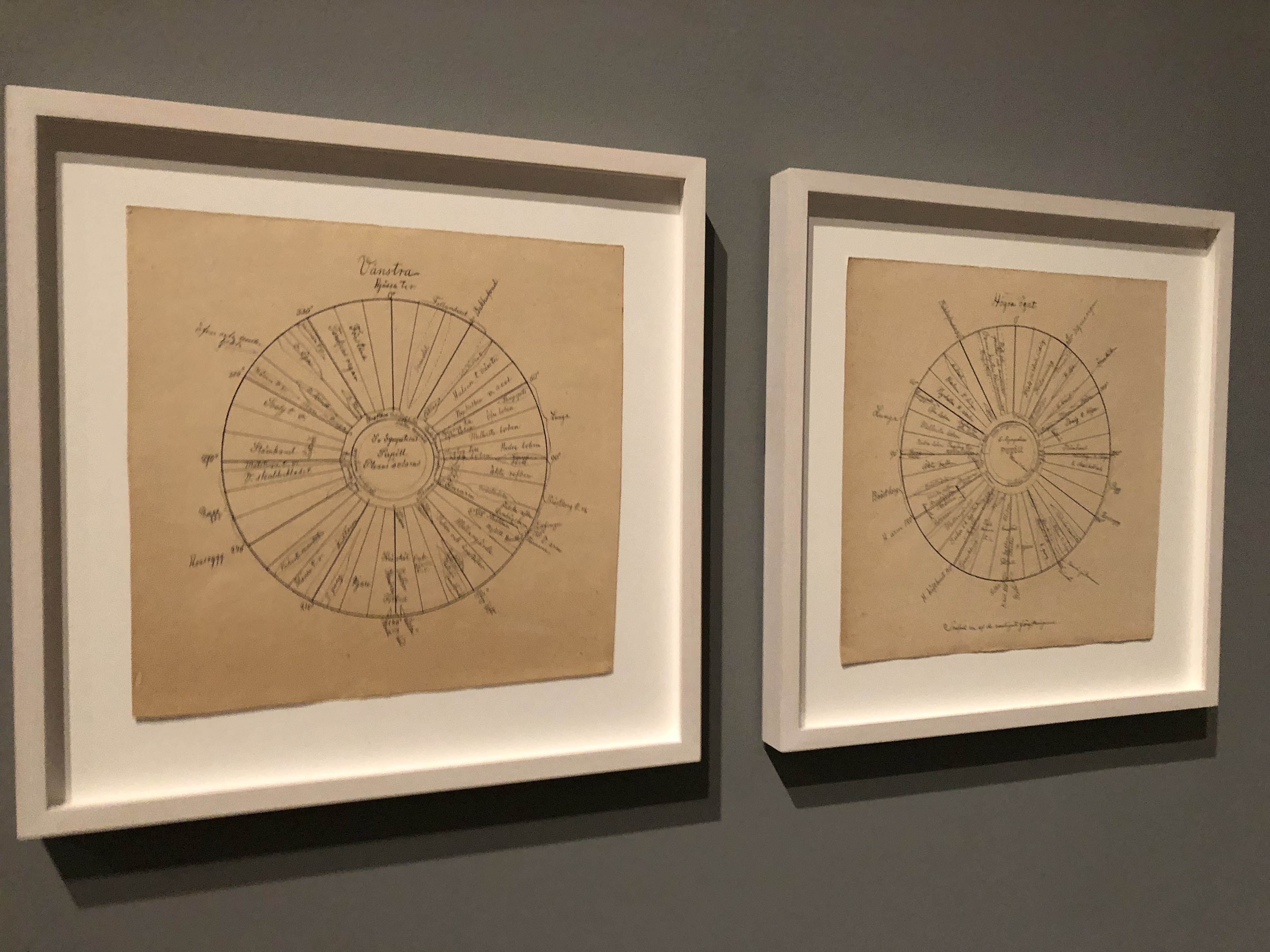

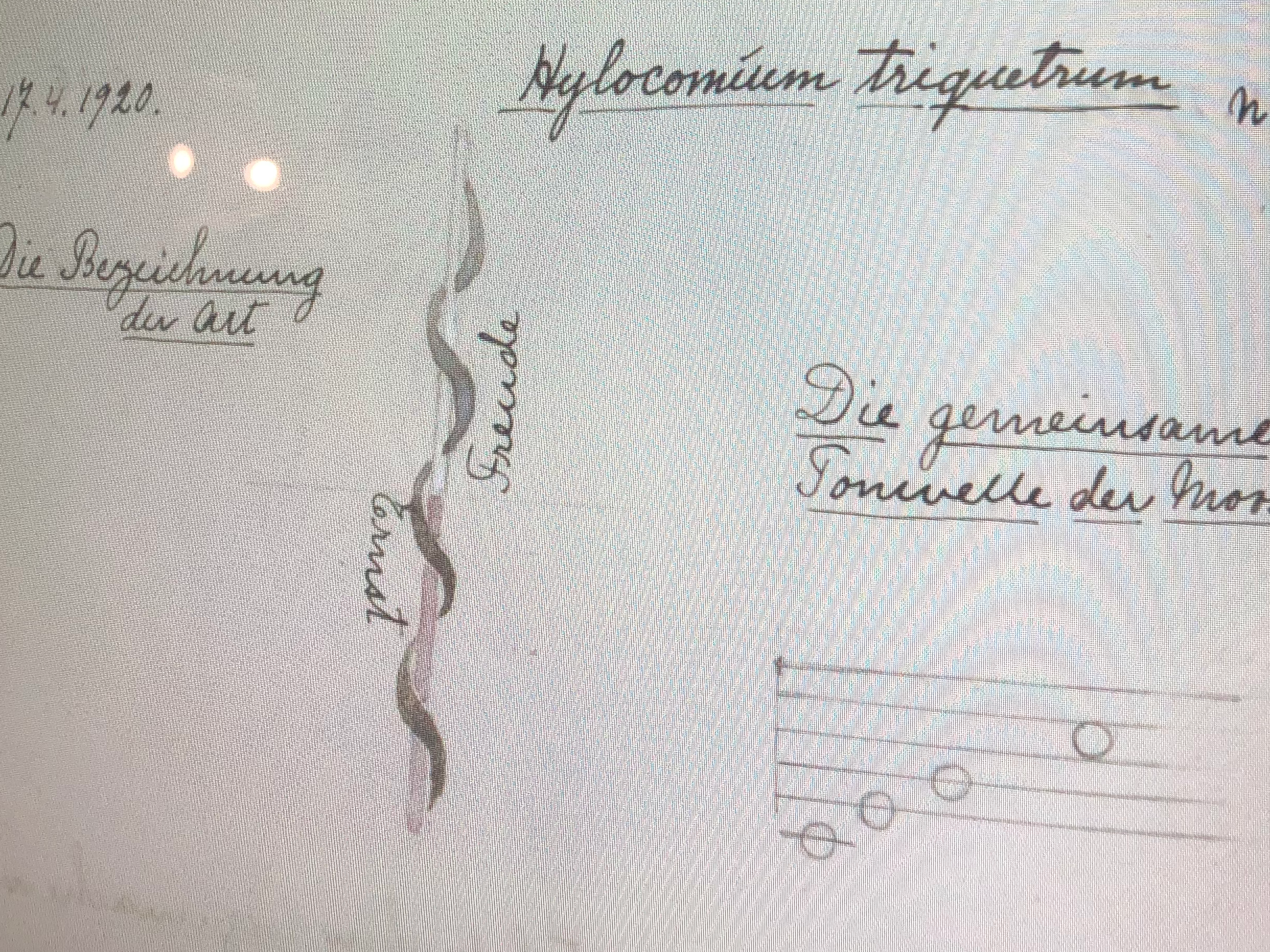

And walking through the rest of the exhibit, I began to learn more about Hilma af Klint and the world in which she worked as an artist. One of the exhibition’s main themes is how af Klint’s artistic process was deeply rooted in the scientific and religious discussions of the time. So artifacts and drawings by Carl Linnaeus and Rudolf Steiner** were placed side by side with af Klint’s sketches, revealing connections between contemporary ideas and her own process.

Left, flower classification diagrams by Carl Linnaeus. Right, diagram sketches by Hilma af Klint.

Though a lot of Rudolf Steiner’s ideas are considered religious pseudoscience today**, I do recognize that he was trying to coherently frame a more unified theory of human existence to come to terms with both spirtual ideology and the latest findings by contemporary scientists that resolved some of life’s mysteries, the unobservable and the observed.

Left, chalkboard diagrams by Rudold Steiner. Right, works by Hilma af Klint.

Even today, I think people who know they should maintain an objective and scientific mindset still turn to religion and spiritual ideas because they desire some sense of meaning in their lives, a connection to something greater than their daily to-do’s. And so in the context of Steiner’s anthroposophy (or “spiritual science” as Steiner called it), I see in af Klint’s work the constant attempts to propose narratives that elegantly tie together the mystical spirit of life and the empirical models of the natural world around us.

Though I didn’t really care for the Christian symbolism in her work, I found myself relating to af Klint’s intent and process in so many ways. I’ve always been intrigued with how people still find meaning and beauty in a more scientific and technologically driven world like Feynman’s description of a flower, and the entirety of Zen and Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. I enjoy coding graphics with p5js and the broader pursuit of using systems of logic and patterns to make art.

Hilma af Klint - Group IX / SUW, no. 1 and 8. The Swan 1915

But most of all, I really wonder what kind of art would af Klint make today, as ChatGPT and Midjourney generative AI has captured the fascination and concerns of artists and the general public. af Klint and Mondrian may well be concerned about the ethics of reusing art, including their own works being fed into training generative image models.

I would like to think that they would also look past generative AI as a tool for remixing creative works and be immensely curious about the machine learning research that went into building those generative models in the first place. My impression from the likes of Geoffrey Hinton, Yann LeCun, and Yoshua Bengio is that fundamental machine learning research does build off an understanding of how humans learn about the world around them. And so I’d bet that af Klint would eagerly sit through a lecture on the history of machine learning and recognize neural networks as major abstractions that distill parts of how people perceive reality.

Some of her quotes and diagrams did suggest an interest in iridology, the study of patterns and colours on the iris of the human eye. I can’t imagine how af Klint would re-purpose her own skills of abstraction and artistry to really engage with the theories and methods of computer vision and deep learning and their sources of inspiration in cognitive science, linguistics, and human anatomy.

Iris Diagnosis Charts by af Klint

I wonder what af Klint would think of convolutional neural networks today, as they essentially look past an image’s raw form of pixels and try to associate relationships between that form’s features and verbal descriptions.

But since I can’t imagine how af Klint would respond to the fascinating theories behind machine learning, I’m ever more inspired to make something of my own in her spirit. Further encouraging me are the various genres her thoughts seem to span, beyond painting and drawing. The exhibit displayed notebook sketches with sheet music sketches and architectural models.

Left, digital scans of af Klint’s notebook which contains sheet music sketches paired with other diagrams. Right, museum model makers’ interpretation of a temple which af Klint sketched and imagined where she wished people could visit to experience her work.

I left the exhibit with a strong sense of how art can take inspiration from emerging science and technology. af Klint really danced with the ideas of her time and produced works that prompted viewers to look past their physical reality and find something transcending that existence. While I don’t think I would agree with the entirety of af Klint’s thoughts word for word, I did feel a strong connection to her process and approach to art and storytelling.

“I am an atom in the universe that has access to infinite possibilities of development. These possibilities I want, gradually, to reveal”

-Hilma af Klint, 1916

I should make sure to drink espresso before every museum/gallery I visit…

___

*So about Piet Mondrian…

There were a few paintings of his I liked here and there. And the exhibit did seem to hint at how, like af Klint, Mondrian was also inspired by science and theological discussions of the time. But honestly those works did not really leave as much of an impression on me.

The few things that stood out to me by Mondrian:

He had a theater design piece! This was surprising at the time I visited, since I only remember Mondrian as a painter (of course now I remember Mondrian was a member of the de Stijl movement)

A lot of his works employ visual patterns that might make fun Processing coding exercises.

**Carl Linnaeus would also attempt to classify human beings into hierarchies or “varieties” based on geography and skin color, thus contributing to the eugenic ideology. Rudolph Steiner’s theosophy found some admiration among future Nazi party members. One should always be cautious in embracing ideas to their fullest extent and question if their application to other segments of society overrides important moral and human values.